As we re-entered Vancouver’s False Creek last weekend, we were greeted by a very sad sight.  A local boat was on the beach after strong overnight winds.  I know this boat.  It’s somebody’s home.

As we re-entered Vancouver’s False Creek last weekend, we were greeted by a very sad sight.  A local boat was on the beach after strong overnight winds.  I know this boat.  It’s somebody’s home.

I don’t know what happened, but I see the same mistakes made over and over again by boaters and it was likely either gear failure or one of the 6 mistakes below.

Many people don’t do any formal training when they learn to sail, or they only take the introductory course and never take the higher courses where you actually learn how to anchor.

After all, “How hard can it be to throw an anchor over the side?â€

Unfortunately, it’s a bit more complicated than that (but not much).  We anchor frequently and we see a lot of goofy stuff.  Here are the 6 most common mistakes that we see:

1. Inadequate Anchor

The vast majority of anchors that you see on the bows of boats in the marina are woefully inadequate. Â Before you even leave the dock, you need to set yourself up for success.

Your $200-400 anchor is going to be holding your $5000-500,000 boat, so spend a little money if you need to. Â Most boats come with inadequate anchors, even new from the manufacturer!

Anchor Type

If you anchor in easy locations in settled weather, you can get away with using most of the common anchor types. Â There will be a very detailed guide to anchor selection coming up in a future article, but here is a short summary from adequate to great:

- CQR: I detest this anchor, but some people have success in easy ground with an over-sized CQR. Â My boat came with one and we dragged it around many an anchorage before we finally dumped it.

- Bruce:  This is somewhat better than a CQR and can be a pretty good anchor if you buy a genuine one (which are no longer made) and oversize it.  The smaller ones don’t penetrate well, and the Lewmar Claw copies are crap.

- Delta:  These are OK anchors.  I wouldn’t buy one, but I wouldn’t necessarily heave mine in the garbage if it came with the boat.

- Danforth:  This is a tough one.  These anchors have the absolute best holding per pound of anything out there and are often the only practical anchor for very small boats.  The problem is that they can jam and not re-set in a wind shift.  I’ve had this happen to me and it left an impression!  Fortress makes the best Danforth style and we carry one for a back-up.

- New Generation Anchors: Â There is much debate over the best new generation anchor, but all of them outperform the older models listed above by a significant stretch. Â Any of the these anchors will do you very well:

- Convex: Sarca Excel

- Hooped Anchors: Manson Supreme, Mantus, Rocna

- Concave With No Hoop: Manson Boss

- Weighted Tip: Spade, Vulcan, Ultra

Anchor Size

Every anchor manufacturer publishes a sizing chart based on boat size. Â Common wisdom is to choose one size up unless you have a compelling reason not to (very small boat, racing, or a bad back and no windlass).

Deltas in particular tend to recommend very small anchors and you should consider going two sizes up.

2. Bad Choice of Location

Your first anchoring step is, of course, to figure out where to anchor.

Choosing the Anchorage

Depending on where you sail, this can be tricky. Â You need to know the forecast and you need some information about the potential anchorages (depth, bottom type, size).

Many anchorages are open in at least one direction, so you’ll first want to figure out which way the wind is forecast to come from.

Many anchorages have challenging bottoms. Â You can find out about the holding from guide books, Active Captain, or other sailors. Â Bottom type is often shown on charts, but may not indicate how good the holding is.

In settled weather or with superior anchoring gear and skills you can tuck into anchorages with poor holding, but make the decision consciously.

You’ll need to know the depth and look at your own draft (how deep your boat goes beneath the water) and the expected tides.  In very deep anchorages, you may be able to anchor by dropping on the steep slope of the bottom and then tying to shore (known as stern tying).

Choosing Your Spot in the Anchorage

This part is really tough sometimes, especially if it’s very crowded.  It takes some judgement to find a spot with good depth that isn’t too close to other boats.

In a crowded anchorage, your swing circles will all intersect and you need to rely on everyone reacting to the wind in a similar way and swinging together.  Stay further away from boats on moorings since they don’t swing through a large circle like you will.

If you’re on rope rode (rode is the anchor chain and/or rope) and the others around you are on chain, then you’ll need to give them a bit more room as you’ll tend to move about more in light winds and they’ll just rotate around where the chain touches the bottom instead of around their anchor.

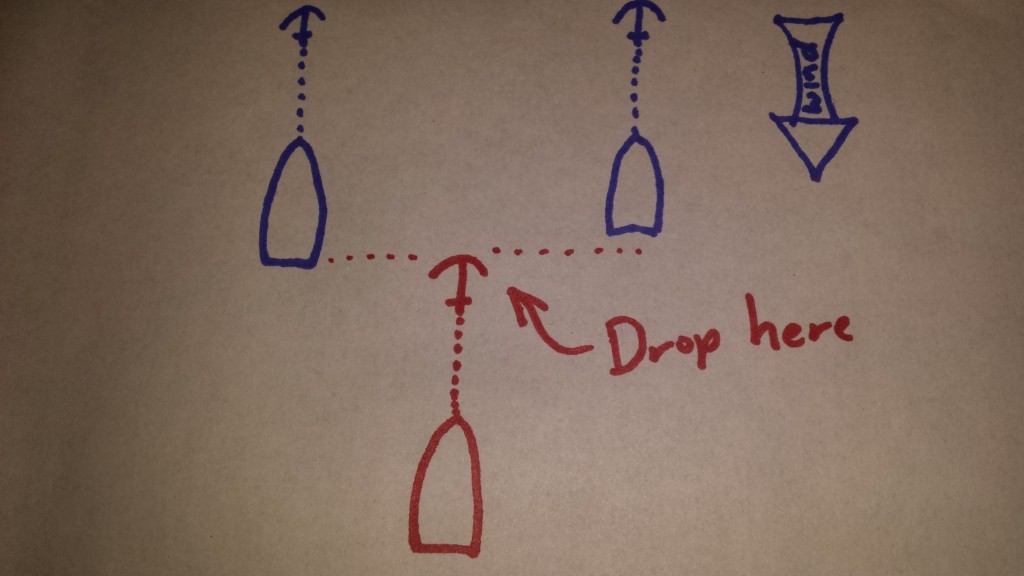

If you are in tight quarters, choose the largest gap you can and then drop your anchor even with the stern of the boat upwind of the gap.  This will take some practice in picturing where you’ll come to rest.

Don’t be shy about picking up and moving if you come to rest too close to another boat.  I’m still working on wedging myself into crowded anchorages and sometimes end up in a different spot than I envisioned.  I’ll just pick up and try again until I’m confident I’m not going to bounce off anyone in the night.

3. Not Enough Scope

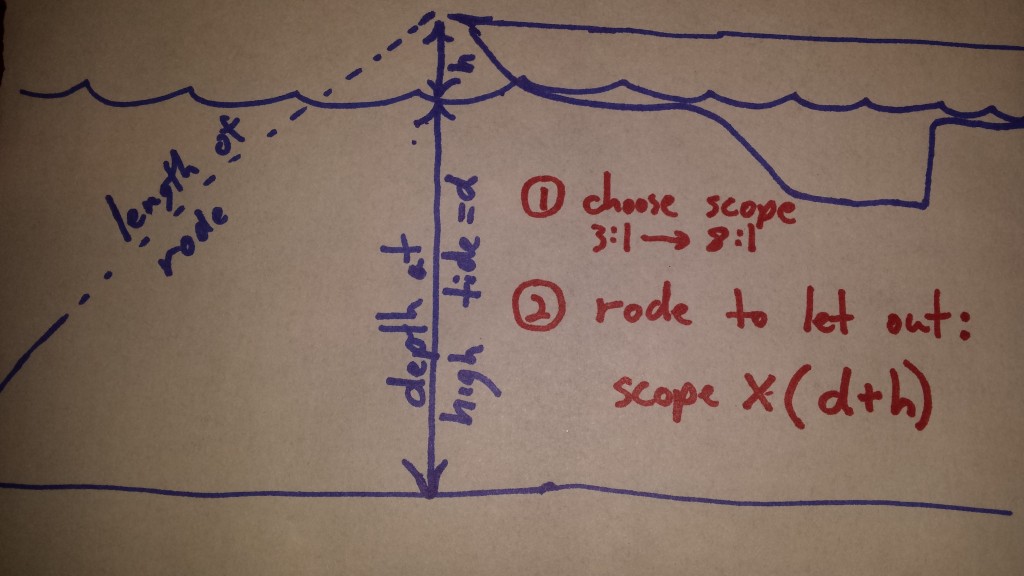

An anchor functions by digging in while it’s being pulled along, horizontal to the sea floor. For this to work, there needs to be enough rope or chain out that the angle of the force is mostly along the floor, not up and down.

It’s surprising how many times you see someone throw out the anchor and then tie it off as soon as it touches the bottom. How could a 35 pound anchor hold a 16,000 pound boat by just resting on the mud?

Scope is measured by the ratio of the height of the bow above the sea bottom to the amount of rode let out. So in 5 meters of water with 2 meters between bow roller and the sea surface, you’d get 3:1 scope by letting out (5+2) x 3 = 21 meters of rode.

Caution: Make sure you know what the depth on your depth sounder actually means!  Some are set to read from the bottom of the keel and some from the waterline.  Here’s the story of a mom alone on a boat with a baby who dragged through a crowded anchorage in the middle of the night because of this easy to make mistake.  She did a heroic job all on her own and saved the day, but had a scary night!

Don’t forget about the tide. In areas with significant tides, you need to have a general idea of the current state of tide and the highest and lowest tide during your stay at the anchorage.

Check the highest tide and then add the additional height to your scope calculation. Also check the lowest tide and make sure you’ll still be floating! Tides vary, so don’t just look at the next low. A good friend of mine made that mistake and was left high and dry when the second low tide was a lot lower than the first.

The absolute minimum scope is 3:1. The more you let out, the better the angle will be up to about 8:1 at which point it makes little difference if you add more. Many people prefer about 5:1 in moderate conditions.

In crowded anchorages you may not have much choice but to go with minimal scope. In the Pacific Northwest, the anchorages are small, deep, and crowded. Luckily, they are also well protected, have excellent holding, and are often dead calm overnight (at least in summer when they’re crowded).  So 3:1 is very common here, whereas 5:1 is more common in other parts of the world with shallower anchorages, more room, and more wind.

Often, if the wind starts blowing hard, it will also blow in one direction, so you don’t really need to worry about swinging circles anymore and can let out more rode. When the wind starts whistling in the rigging at 3am, you’ll go up top to find everyone in the anchorage letting out more scope in their underwear and headlamps.

If the wind does come up and you find that you’re slowly dragging, your first step (if you have room behind you) should be to let out more scope. Go to 8:1 if you can and see if that stops the drag.

4. Not Laying Out the Rode

When the anchor hits the bottom and you start paying out the rode, the boat needs to be in motion. If you pile it all on top of the anchor, it will foul the anchor and you won’t get a good set.

Lay the rode out evenly so it isn’t piled on the anchor or wrapped around a rock and so you won’t shock load the anchor when you go to set it.

5. Not Setting the Anchor

For some reason, very few people actually set their anchor. They just let out the rode, tie it off and go below. How do they know the anchor will hold them?

Setting the anchor does three things.

- It digs the anchor into the sea floor in a controlled progressive way.  Otherwise, if the wind comes up suddenly and the boat gains momentum, no anchor will be able to grab on and hold as it’s pulled rapidly along.

- It proves that the anchor will hold. Sometimes you drop onto a weedy patch or foul the tip in a tin can or something. You need to test out your anchoring job to know you’re safe for the night.

- It shows you where you’ll end up in relation to shore or other boats if your rode gets straightened out by heavy winds.

Setting the anchor:

Once the rode is laid out at the correct scope, tie off rope rode or attach a chain hook to the chain (you don’t want to be pulling directly on the windlass). Don’t apply a snubber yet (see number 6 below).

The person at the bow should signal the helmsman to slowly start to bring up the power in reverse. This needs to be a gradual process as you slowly take the slack out and let the anchor orient itself and get a grip on the bottom.

Once all the slack is out and a moderate pressure is being applied to the rode, the person on the bow should put their foot on the rode, and look out sideways to find a “range:†two objects, one close and one far, which will show if the boat is moving backwards.

Signal for more power and then watch the range closely and feel the chain. As the power is gradually increased to full reverse, you should initially feel the chain jerking a bit as the anchor sets and see the boat move back slightly. It should then stop and hold absolutely still.  The two objects in that make up your range will stay in the same location relative to each other.

Apply full power for 30 seconds to a minute. After you have proven to yourself that you’re well set, gradually let off the power. If you let it off too quickly, the chain will drop to the ground and slingshot the boat forward.

6. Not Using a Snubber

If you’re anchoring with all chain, then you have a very strong but rigid system that will shock load the anchor and your boat if there are waves or if the boat sails at anchor in heavy winds.

A nylon “snubber†should be used. This is just a 30’ piece of rope that puts a bit of boing in the system. I prefer to keep mine dry by tying it to my midship cleat and running it along my deck and then over the bow roller where it’s tied with a rolling hitch just above the water line (or you can use a chain hook if you prefer).

Don’t forget to let out enough slack in the chain to allow the snubber to stretch and then tie off the chain as well as a back-up in case the snubber lets go.

It’s natural to be nervous about anchoring at first. I still have butterflies in my stomach when I come into a tricky or crowded anchorage and I feel like all eyes are on us as we anchor (well, they probably are, but they’re mostly friendly eyes, I promise you!).

If you avoid the 6 mistakes above, you’ll be able to have many confident, sleep filled nights knowing you’ll be right where you expect to be when you wake up in the morning.

If you want to learn more, you can check out the highly rated Nautic Ed course on anchoring.  It’s inexpensive and was designed by the author of Happy Hooking – the Art of Anchoring.

Have you made one of these mistakes? Â Share your tips or misadventures in the comments below.